Sign a Stillborn Over to a Hospital What Became of the Baby

- Research article

- Open Admission

- Published:

Incidence of stillbirth and perinatal mortality and their associated factors among women delivering at Harare Maternity Hospital, Zimbabwe: a cross-exclusive retrospective assay

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 5, Article number:9 (2005) Cite this article

Abstruse

Background

Decease of an infant in utero or at birth has always been a devastating experience for the mother and of concern in clinical do. Babe bloodshed remains a claiming in the intendance of pregnant women worldwide, but particularly for developing countries and the need to understand contributory factors is crucial for addressing appropriate perinatal health.

Methods

Using data available in obstetric records for all deliveries (17,072 births) at Harare Maternity Infirmary, Zimbabwe, nosotros conducted a cross-sectional retrospective analysis of a ane-year data, (1997–1998) to assess demographic and obstetric chance factors for stillbirth and early on neonatal death. We estimated chance of stillbirth and early neonatal expiry for each potential risk factor.

Results

The annual frequency of stillbirth was 56 per 1,000 total births. Women delivering stillbirths and early neonatal deaths were less likely to receive prenatal intendance (adjusted relative hazard [RR] = 2.54; 95% confidence intervals [CI] ii.19–2.94 and RR = ii.52; 95% CI 1.63–3.91), which for combined stillbirths and early neonatal deaths increased with increasing gestational age (Hazard Ratio [Hour] = 3.98, HR = seven.49 at 28 and 40 weeks of gestation, respectively). Rural residence was associated with hazard of infant dying in utero, (RR = i.33; 95% CI i.12–one.59), and the chance of death increased with increasing gestational age (HR = 1.04, Hr = i.69, at 28 and 40 weeks of gestation, respectively). Older maternal age was associated with risk of death (HR = 1.50; 95% CI 1.21–1.84). Stillbirths were less likely to be delivered past Cesarean section (RR = 0.64; 95% CI 0.51–0.79), merely more than likely to exist delivered as breech (RR = 4.65; 95% CI 3.88–5.57, as were early neonatal deaths (RR = iii.38; 95% CI one.64–half dozen.96).

Conclusion

The frequency of stillbirth, especially macerated, is high, 27 per 1000 total births. Early prenatal intendance could help reduce perinatal death linking the woman to the health care organization, increasing the probability that she would seek timely emergency care that would reduce the likelihood of expiry of her infant in utero. Improved quality of obstetric intendance during labor and delivery may aid reduce the number of fresh stillbirths and early neonatal deaths.

Background

Perinatal mortality remains a challenge in the care of meaning women worldwide, peculiarly in developing countries [1–3]. To address the problem of perinatal mortality, factors associated with stillbirth, a major contributor of over fifty% of perinatal deaths in developing countries, [four] must exist understood. Stillbirths are both common and devastating, and in developed countries, about one tertiary has been shown to be of unknown or unexplained origin [4, 5]. Every bit is the perinatal bloodshed rate, the stillbirth ratio is an of import indicator of the quality of antenatal and obstetric intendance [2, 3, 6], but studies have not distinctively differentiated the frequency of and chance factors for diminished versus fresh stillbirths. Agreement the distribution of fresh and macerated stillbirths and deaths within the immediate postpartum menses may help identify the quality of antenatal and obstetric care available to the significant women and prioritize advisable intervention strategies. Diminished stillbirths are often associated with insults that occur in utero during the antenatal period, while fresh stillbirths and early on neonatal deaths or bloodshed (ENNM) may suggest problems with the care bachelor during labor and at delivery [3, 7, 8]. Few studies from Zimbabwe [nine–11], have examined frequency of perinatal bloodshed and how this outcome varies across important demographic subgroups. Studies from developing countries have not considered the frequency of macerated and fresh stillbirths and their relationship to preterm birth or low nativity weight (LBW) [1], and no such report has been conducted in Zimbabwe.

In Zimbabwe, perinatal mortality remains unacceptably high. In Harare, the uppercase city, perinatal mortality declined from 83 per 1,000 live births in 1978, to 34 per ane,000 live births in1984 and has changed little since and then [12, thirteen]. In 1983, an audit of all births occurring within the Greater Harare Maternity Unit (GHMU), which comprises of Harare Motherhood Hospital (HMH) and the 12 municipal clinics in Harare, estimated perinatal mortality to exist 34.5 per one,000 live births, with preterm birth being the leading cause of perinatal mortality, accounting for 19.3% of perinatal deaths [fourteen]. By 1989, perinatal mortality had risen to 47 per one,000 alive births [12, xiii]. Iliff and Kenyon [12, 13] estimated that an increment in the number of and bloodshed from preterm births accounted for nigh one-half this increase. In the aforementioned study, stillbirth ratio was estimated to be 26 per 1,000 total births. A more contempo study estimated the frequency of stillbirth at HMH to exist 57 per 1,000 total births [9], which, using conservative assumptions, translates to 33 per one,000 total births for the GHMU. Prevention of perinatal deaths is critical, especially those associated with LBW and preterm birth, since intuitively, infants who are born early or small accept increased adventure of morbidity and bloodshed [2, iii, 9, 14].

Data on the frequency and distribution of adverse birth outcomes are important for planning maternal and child health care services in developing countries, and noesis of local patterns of morbidity and mortality is essential for improving antenatal and obstetric intendance. Ensuring a condom and good for you commitment for both mother and kid is a priority of the Zimbabwe health care delivery organization and is an essential component of safety maternity initiatives. In this preliminary study, we assessed the contribution of socio-demographic and reproductive/obstetric run a risk factors to the frequency of fresh and diminished stillbirth and ENNM over a one-yr period at HMH, in Zimbabwe.

Methods

The study was carried out at HMH, the largest referral hospital in Zimbabwe. The study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and the Medical Research Council of Republic of zimbabwe, and permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Ministry building of Health in Zimbabwe, HMH and from the Harare Urban center Wellness Section.

The study methods have been described elsewhere [9]. Briefly, information on all births occurring from October 1, 1997, through September 30, 1998, at HMH was bathetic from the maternity delivery registry records. For each nascence, data was abstracted on the date of birth, residential surface area of the woman (rural/urban), whether the mother attended prenatal intendance or non, maternal historic period and parity, estimated gestation, birth weight; sex and vital status of the baby at birth, whether the infant was a single or multiple commitment, and the type of delivery. It was not possible to link births from multiple gestations in this data fix. A woman was considered to have received prenatal care when she had at least one visit for prenatal intendance during her pregnancy. Parity was the number of previous pregnancies catastrophe afterward 20 completed weeks of gestation including stillbirth (categorized equally 0, 1 to 2, and more than ii pregnancies). Blazon of delivery denoted whether the babe was delivered vaginally presenting as cephalic, face up to pubis or breech; vaginally with instrumental assistance; or past Cesarean section.

Eligibility criteria for this report were based on the WHO definition of viability, that is, a nascence weight of at least 500 grams gestational historic period at least of 20 weeks [xv]. Births without information on vital condition were excluded. A stillbirth was defined as intrauterine death of a fetus weighing at least 500 grams after xx completed weeks of gestation occurring before the complete expulsion or extraction from its mother. A fresh stillbirth was defined as the intrauterine expiry of a fetus during labor or commitment, and a macerated stillbirth was defined as the intrauterine death of a fetus onetime before the onset of labor, where the fetus showed degenerative changes [xv] as reported in the obstetric records past the attention doctor/midwife. An ENNM was defined as a death that occurred within the first hour of life.

Gestational age (GA) at nascency was estimated by the number of days between the get-go twenty-four hours of the last menstrual period (LMP) and date of birth expressed in completed weeks after LMP and a clinical estimate as recorded in the maternity delivery record. Preterm nascency was defined as a nascence occurring at or earlier 37 completed weeks of gestation. A post-term birth was defined as a birth occurring after 44 weeks of gestation. Nascence weight was divers as the offset measurement of body weight, usually in the first hour of life, measured to the nearest gram. A LBW nascency was defined every bit the nascence of an infant weighing less than ii,500 grams at birth irrespective of gestational age. We too defined three LBW subgroups; term LBW nascence, preterm LBW birth and very LBW birth defined as infants weighing below 1,500 grams. A high nascency weight birth, based on the upper tenth percentile of our nascence weight distribution, was defined as the birth of an baby weighing above 3,500 grams.

A total of 18,149 births were recorded in the 12-month study period. On average betwixt fifty to 60 deliveries occurred daily. We excluded 32 (0.2%) births beneath 20 weeks of gestation, 68 (0.4%) that did not have information on vital condition, 78 (0.4%), that weighed below 500 grams at birth and 795 (4.iv%) that were missing information on nascency weight or estimated gestation. Finally we excluded an boosted 103 (0.half-dozen%) births for which birth weight/gestational age combination were implausible based on the algorithm advocated by Alexander et al. [16], leaving 17,072 births for this analysis.

Statistical analysis

The numbers of fresh, macerated, and un-typed stillbirths are presented as a proportion of all births, and ENNM are presented as a proportion of live births. To examine predictors of these outcomes, cross-tabulations by each covariate were examined using chi-square tests of homogeneity. Equally the complete population of births over a one-twelvemonth period within the infirmary was ascertained, we could directly estimate the risk of stillbirth and ENNM for each covariate. In the unadjusted analyses, relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each demographic and reproductive risk factor using EP-INFO 2000. All 17,072 eligible births were included for stillbirth analyses. Given the differences in risk for singleton and multiple births, the subsequent multivariate analyses are express to singleton births, therefore sixteen,023 singleton births were used for the stillbirths and combined stillbirth and ENNM analyses. For ENNM only analyses, fifteen,117 live singleton births were included.

Multivariable generalized linear regression models with a log-link function and binomial error using SAS [SAS Constitute Inc., Cary, NC, United states of america] version 8.1, were used to model each outcome. A log (rather than logit) link function and binomial errors were used to permit interpretation of relative risks (rather than odds ratios). Relative risks of stillbirth and 95% confidence intervals were calculated after adjusting for maternal age, residence, prenatal care, parity, baby sex and type of delivery. As estimates were not stable due to collinearity, we combined births delivered as face to pubis with those of normal vaginal delivery for the type of delivery analysis, adjusting for maternal age, residence, parity, and baby sex activity.

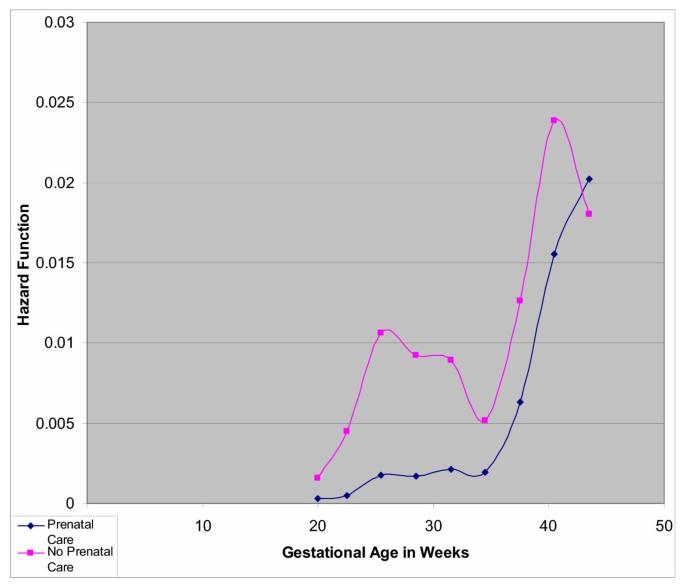

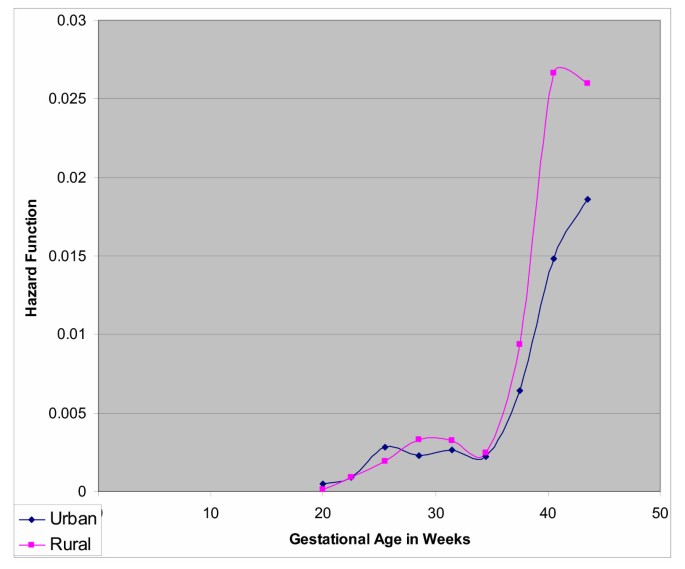

Recent epidemiological literature has suggested at least two alternative methods of computing the probability of stillbirth by GA, with the differences being in the definition of the denominator [17, xviii]. I method calculates the GA-specific probability of stillbirth equally the number of stillbirths divided past the number of births at a given GA. A 2d method calculates the GA-specific gamble of stillbirth as the number of stillbirths at a given GA divided by the number of fetuses at the given GA even so remaining to be born [17–xix]. We provide estimates using the first definition in Tables ii and Additional files ane and 2, and apply the second definition in Tables 3 and 4 and Figures i and 2. Covariate furnishings on gestational age-specific mortality were estimated using Cox regression model with estimated gestation at birth as the time variable. Gamble ratios (HR) for stillbirth and 95% CI were calculated [17, 18]. All 16,023 singleton births were used for this analysis, and stillbirths and ENNM were combined as outcomes of involvement [17, xviii]. The interaction between each covariate and time (GA) was tested for evidence of non-proportion hazards. Covariates with no show of non-proportion hazards (maternal age, babe sex and parity) were refitted without the interaction term. For covariates with evidence of non-proportion hazards (residence and prenatal care) we also calculated the hazard of death at 20, 28, 32, 36, 40 and 42 weeks of gestation. The probabilities of decease at each stage of GA were estimated using life tables for prenatal intendance and for urban versus rural residents, and are presented in Figures 1 and 2.

Probability of Combined Stillbirth and Early Neonatal Death among sixteen,023 Singleton Deliveries by Prenatal Care at Harare Maternity Hospital; October 1997 through September 1998

Probability of Death amidst 16,023 Singleton Deliveries by Residence at Harare Maternity Hospital; Oct 1997 through September 1998

Results

Demographic and obstetric risk factors of stillbirth by type

Of the 959 stillbirths, 201 (21%) were fresh and 458 (48%) were diminished stillbirths; the type of stillbirth for 300 (31%) births could not ascertained from the bachelor obstetrical records. The almanac stillbirth ratio at HMH was 56 per 1,000 full births, of which 12 per i,000 were fresh stillbirths, 27 per 1,000 were macerated stillbirths, and 17 per one,000 were for stillbirths whose type was not indicated in the obstetric records (Table 1). Age of mothers ranged from 10 to 50 years. Most mothers were twenty to 35 years old, with a mean age at delivery of 24.six years. Most mothers (86%) resided in urban areas. Women nowadays belatedly for prenatal care, GA less than 28 weeks accounted for 384 singleton births, of which 180 (47%) did non receive prenatal care. Information technology is uncommon in Republic of zimbabwe for women to nowadays for prenatal care prior to 28 weeks of pregnancy [9, 20], and in the rural areas women could present at a health middle at the fourth dimension of labor if they are having difficulty. Near 45% of the women were primiparous, with parity ranging from 0 to 12. The mean age of mothers with parity of 0, was 20.7 (range 10–41 years), compared to 27.seven (range 14–l) for women with parity i and more. Every bit expected, there were slightly more than male person than female births. A total of 17.5% of the deliveries were past Cesarean section, and an additional two.ii% required some grade of instrumentation during commitment, while 5.9% of the births were either breech or face to pubis presentations. Near 6% of the infants were from multiple gestations, and in crude analysis, multiple gestation births were less likely to be macerated stillbirths (RR = 0.57; 95% CI 0.35–0.93), but more likely to die in the first 60 minutes of life (RR = ane.88; 95% CI 1.12–three.14).

Boosted file 1 presents the crude relative risks of stillbirth by type of demographic and reproductive characteristics of the study population. Young mothers were less likely than older women (RR = 0.73; 95% CI 0.61–0.88) to deliver a stillborn infant, with the reduction in adventure particularly axiomatic for macerated stillbirth (RR = 0.72; 95% CI 0.56–0.93). In contrast, women to a higher place 35 years had a 59% increased risk of stillbirth and 43% increase in the likelihood of delivering a macerated stillbirth. Rural women delivering at HMH had a 24% increased chance of stillbirth compared with women who resided in urban areas. Women who did not receive prenatal care consistently had over a 2.3-fold increment in the adventure of stillbirth of whatsoever type. Compared to a normal vaginal delivery, breech deliveries were over 4.vii times more likely to be stillbirth, while births by Cesarean section were less likely to issue in whatsoever blazon of stillbirth. Delivery past instrumentation was ii.two times more probable to issue in a fresh stillbirth than was normal vaginal commitment.

Additional file two presents adjusted relative risks for stillbirth by demographic and reproductive characteristics. Except for parity, which is correlated with maternal historic period (Pearson coefficient r = 0.76 p-value = 0.0001), the risks did non modify in the adapted assay. Overall, risks for un-typed stillbirths did not differ from those for fresh and macerated stillbirths, except for residence and commitment by Cesarean section.

Demographic and obstetric risk factors of ENNM

The early neonatal mortality ratio was 9 per m alive births. Table ii presents the distribution and take chances for ENNM by demographic and reproductive characteristics. Mothers under 20 years old were 69% more than probable than mothers twenty to 35 years of age to deliver an infant who died within the outset hour of life, and similarly, risk for primiparous women was 81% compared to multiparous women. Male infants had a 69% increased take a chance of dying within the offset hour of life. Women who did not receive prenatal intendance consistently had over a ii.4-fold increment in the risk of ENNM. Compared to a normal vaginal delivery, breech deliveries were 9.9 times more likely to terminate up equally ENNM. Delivery by instrumentation was three.vii times more likely to result in ENNM than was normal vaginal delivery. Except for maternal historic period and parity the risks remained the aforementioned or elevated in adjusted analysis.

Relationship of mortality to demographic and obstetric factors

Table three presents the rough hazard ratios for mortality (stillbirths and ENNM combined) for demographic and obstetric characteristics that had abiding hazard ratios over GA. In that location was a 50% increased take a chance of death for mothers over age 35 years compared with mothers xx to 35 years of age. There was a 20% increased risk of expiry for mothers parity above 2 compared with mothers with parity one to two. Baby sex was non significantly associated with mortality.

Relationship of bloodshed to prenatal care and residence

Table four presents crude hazard ratios for mortality (stillbirths and ENNM combined) for demographic and obstetric characteristics for which hazard ratios change over GA. These variables included prenatal care and residence. The hazard ratio for prenatal care decreased with increasing gestation, from four.76 at 28 weeks to 1.35 at 42 weeks. Figure 1 depicts the risk function by GA comparing mothers who did and did non receive prenatal care. At xx weeks, the adventure functions for mothers who did not receive prenatal care and those who did are similar. Withal, because of the low probability of death earlier week 35 among those receiving prenatal care, the relatively higher probability amongst those non receiving prenatal care results in a high relative take chances. Afterwards week 35, the mortality (stillbirths and ENNM combined) hazard in both groups increases proportionally, but for those without prenatal intendance remain at higher run a risk and the event is attenuated at 42 weeks.

As gestation increased, the risk of mortality for rural residence increased, from i.04 at 28 weeks to 1.69 at xl weeks and 1.84 at 42 weeks of gestation (Table 6). Figure 2 depicts the risk part by gestational age comparing rural and urban residence. Upwards to 35 weeks the hazards are very similar, beyond 35 weeks, the hazards increase proportionally for both groups, but predominantly higher for births from mothers who resided in rural areas.

Distribution of stillbirth and ennm past birth weight and ga categories

Boosted file 3 shows the distribution of stillbirth and ENNM past birth weight and GA categories, using the traditional methods (birth weight-specific mortality, where LBW is analyzed equally preterm LBW, term LBW) [18]. Sixteen percent of all stillbirths were LBW and 17% were preterm. Virtually iii% of neonatal deaths were LBW, and 3% were preterm births.

Word

This newspaper evaluates the distribution of and take a chance factors for fresh and macerated stillbirth and ENNM among mothers giving birth at the largest hospital serving Harare, Zimbabwe. The proportion of macerated stillbirths in Harare is higher than in more adult countries, suggesting the presence of insults to the developing fetus and the need for timely screening and direction of chronic weather and infections. A considerable proportion of the stillbirths were fresh stillbirths, and the frequency of ENNM was high, suggesting the need for improved obstetric care and availability of emergency services during the delivery menstruum. Lack of prenatal care was associated with increased risk of stillbirth and ENNM whether we analyzed using traditional methods (gestational age-specific mortality) [eighteen] or with GA every bit a time-varying factor equally argued by other experts [21–23]. Similarly, rural residence was associated with increased risk of all stillbirth and ENNM whether we analyzed using traditional methods (gestational historic period-specific mortality) or with GA every bit a time-varying factor. Just well-nigh chiefly, using GA equally a fourth dimension-varying factor clarifies where and when the risk of expiry is more prominent. Fresh or diminished stillbirths and ENNM were more likely to be delivered breech, but less likely to exist delivered past Cesarean section. Cesarean section appears to protect against stillbirth in this population. Fresh stillbirths and ENNM were also associated with commitment by instrumentation.

The incidence of stillbirth, 56 per 1,000 total births we report for HMH, is higher than the 26 per 1,000 full births reported by Iliff and colleagues using 1989 data from HMH and 9 Harare municipal clinics [12, 13], and higher than the 45 per i,000 live births at Mpilo Motherhood Hospital [24], some other large referral hospital in the 2nd largest city in Zimbabwe. Our findings differ from previous Zimbabwean studies because HMH is the largest referral center in this state, and would be expected to take higher bloodshed rates than other hospitals referring their most complicated cases. When we recalculate our rates based on the number of deliveries in the GHMU, 56% of which occur at HMH [9, 25], and bold no stillbirths occurred in the clinics, we estimate a population-based stillbirth ratio of 33 per 1,000 full births, a figure more comparable to that reported by Iliff and colleagues.

In this population, more stillbirths were macerated, suggesting existence of problems linked to the antenatal period, which could be related to built malformations [two, 4]; obstetric hemorrhage; preclampsia [2, iv–6, 26]; infections such equally syphilis [7, 8, 26, 27]; or existing maternal chronic conditions such as hypertension, cardiac disease, and diabetes [2, 4–vi], none of which our study had the power to evaluate. Smoking, which is an important factor specially in developed countries, was not a cistron for this population [28]. Fresh stillbirths contribute ane.two% of all births while ENNM contribute 0.9% of live births at this institution, and both are likely to be related to fetal hypoxia [ii, 12, 26], built malformations [2, iv, 12], quality of delivery care given to a woman during labor and delivery, and poor admission to emergency obstetric intendance.

As would be expected, lack of prenatal intendance was consistently and strongly associated with stillbirths and ENNM, similar to what other studies have reported [7, 29–31]. Although women in Republic of zimbabwe normally brainstorm prenatal care at 28 weeks of gestation a considerable number will present at hospital before that time for a trouble related to their pregnancy leading to an adverse birth outcome [[9, xx], and [28]]. Had the agin nascence result not occurred prior to 28 weeks of gestation, these women could accept had an opportunity to present for prenatal care, later in their pregnancy equally is common for almost women in Republic of zimbabwe. The chance of bloodshed (stillbirths and ENNM combined) increases with increasing GA before 35 weeks of gestation, but decreases proportionally thereafter. In that location was a crossover of risk of mortality by prenatal care much after in the course of pregnancy, at 42 weeks of gestation, a phenomenon reported but at earlier gestational historic period past other studies [17–19]. Thus, the risk of mortality was much college for women who did not receive prenatal care compared to those who did in the earlier gestational ages, and was moderately college proportionally after 35 weeks of gestation, and was adulterate at term. In developing countries, prenatal care, even if merely attended one time, remains an important gene in obstetric care, as this may be a critical linkage betwixt the woman with maternity care services [ix, 28]. In contrast, research findings in middle-income countries emphasize the importance of the number of prenatal intendance visits and the adequacy and quality of prenatal care services. WHO recommends using prenatal care as a strategy for improved obstetric care [32]. Our data suggest that prenatal care may help ensure that interventions occur in a timely manner.

Rural residence was associated with increased risk of all stillbirths equally reported by previous studies [9, 28]. The chance of mortality (stillbirths and ENNM combined) increased with increasing GA, like to other study reports [17–19]. Before 35 weeks both rural and urban women have a like take a chance of mortality. Although the risk of mortality increases proportionally to term for both groups, rural women have a higher risk of having their infant dying in utero and within the first hour of life. Prior to 28 weeks a considerable number of women from rural residence did not receive prenatal care, 39 (10%). Later on 35 weeks rural women who end up with their infant dying in utero or inside the fist hr of life might have been women referred to HMH from rural centers with a condition/complication related or leading to the adverse nascency outcome. Caution should be taken when interpreting this finding, because we take two artifacts. Intuitively, after 35 weeks, women who did not receive prenatal intendance are primarily from rural areas and were likely not to receive prenatal care throughout their pregnancy. Secondly, we do not have the counter population (rural women who attended prenatal care) in our denominator.

For maternal age, infant sex activity and parity in our study, which were not time-dependent, using either traditional methods (gestational age-specific mortality) [18] or the analysis where GA is a time varying gene did not change the risk of bloodshed (stillbirths and ENNM combined). But, using GA as a fourth dimension-varying gene for the assay helps us to understand further the relationship betwixt some of the maternal factors and mortality, which otherwise would take been missed. For prenatal care and residence, we were able to show how the gamble of bloodshed was distributed at each stage of GA. We were able to separate furnishings at early periods versus later stages in pregnancy, which is useful for wellness-care planners, policy makers, and implementers, in terms of targeting resources. For case, for prenatal care, we were able to show that the risk of morality is high at early gestation. The chance of mortality persists later in pregnancy, merely decreasing proportionally throughout pregnancy, beingness higher for women who did not receive prenatal care. This finding suggests a need to focus and emphasize on early booking and the critical part of prenatal care in developing countries. With regards to residence, knowledge that infants of rural women who get referred to urban institutions have the highest take a chance of bloodshed may advise the need to pay more attention during the antenatal period and to meliorate the referral system and emergency care services.

Stillbirths, irrespective of type, and ENNM were less probable to be delivered by Cesarean section. Information technology is conceivable that factors leading to stillbirth may cause mothers to accept a Cesarean section, but our results show that Cesarean department was consistently protective of either stillbirth or ENNM. This finding may suggest that obstetricians are careful not to perform Cesarean section unless it is indicated for stillbirths, or ENNM, or that whenever a Cesarean section is performed, information technology saves life of the infant.

Stillbirths and ENNM were likely to exist delivered breech. For fresh stillbirths and ENNM, this finding is consistent with the clinical observation that considering of the nature and dynamics of this type of commitment, these infants are likely to die during or at delivery [nine, 28]. Similarly, infants delivered past some form of instrumentation were more likely to dice within the first hour of life. For diminished stillbirths, this finding may exist more than related to preterm infants and would exist consistent with the clinical observation that the infants turn to optimal nativity presentation at about 34 weeks of gestation. Near 242 (47%) of singleton births delivered as breech were preterm. Intuitively, infants that are at risk considering of their pocket-sized size and level of maturity are likely to face the boosted risk of breech presentation.

Maternal historic period furnishings were common in stillbirths, consistent with other studies [33–35]. But the furnishings of maternal age were more prominent for diminished versus fresh stillbirths, again strengthening the possibility that maternal chronic disease conditions in afterwards years of life may play a pregnant role. Additionally, older mothers were at greater risk for stillbirth, merely lower risk for neonatal death. The rough hazard for young maternal age, which was similar to crude risk for primiparity for early on neonatal births, was attenuated after decision-making for residence, parity, prenatal care and infant sexual activity.

This study has some limitations. Every bit the study was a retrospective analysis of information obtained from commitment logs, we were unable to examine take chances factors such as chronic and comorbid atmospheric condition, congenital malformations, obstetric complications, and infections. Although we could non identify the stillbirth status of virtually one-third of stillbirths, hazard estimates for un-typed stillbirths were like to those for fresh and macerated stillbirths. Arguably, focusing solely on births within HMH raises concerns well-nigh option bias. Yet, when nosotros adjust our estimated rate to the base population, our rates are comparable to those previously reported [9, 12–14]. Information on gestational age was limited to the clinicians' estimate and LMP data reported as weeks recorded in the obstetric log, thus some mistake in the classification of preterm births is likely [36, 37]. Regardless, this airplane pilot written report is one of the few to characterize socio-demographic and reproductive take chances factors for stillbirth and ENNM in this population [9]. Our ability to distinguish risks for macerated and fresh stillbirth has direct implications on quality of care given to pregnant women in Republic of zimbabwe.

We were non able to show risk by combined birth weight and GA categories, which would otherwise be important for clinicians [17–nineteen], [38, 39], for to do so is incommunicable every bit birth weight varies with GA [17]. Therefore, it would exist not feasible to put both variables in the same model. Our use of GA as a time-varying variable in this analysis helps anticipate and define where chance occurs in the GA continuum.

Conclusion

Our findings propose that earlier perinatal intendance could assist in early identification and treatment of risk factors for macerated stillbirth, especially those that are preventable. Zimbabwean women enter prenatal intendance tardily in pregnancy, booking at 28 weeks or later [nine, 29–31]. Constructive programs to decrease the frequency of stillbirth may require that entry to prenatal care begin by at to the lowest degree 20 weeks of gestation. Increased focus on wellness education programs, which emphasize the benefits of prenatal care and early booking in the first trimester or by 20 weeks of pregnancy, is needed. Before booking for prenatal care creates a critical linkage between the adult female and the health care system, which may increase the probability that the woman will seek emergency care in a timely manner. In Zimbabwe, more focus is needed on the timing and adequacy of care in maternal and kid health programs, and more research is needed on barriers to early on entry to prenatal care.

At that place is also a need to improve quality of care and access to emergency intendance during labour and delivery to reduce the number of fresh stillbirths and ENNM. Cesarean section should be made readily bachelor as it improves birth outcomes. Further studies should comprise data from women served past the entire GHMU, to ameliorate babe mortality and morbidity in Zimbabwe.

References

-

Kramer MS: The Epidemiology of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes; An Overview. J Nutr. 2003, 133 (5 Suppl two): 1592S-1596S.

-

Kumar MR, Bhat BV, Oumachigui A: Perinatal mortality trends in a referral hospital. Indian J Pediatr. 1996, 63 (three): 357-361.

-

Kambarami RA: Levels and risk factors for mortality in infants with nativity weights between 500 and 1800 grams in a developing land: a infirmary based report. Cent Afr J Med. 2002, 48 (eleven/127): 133-136.

-

Cnattingius S, Stephansson O: The Epidemiology of Stillbirth. Semin Perinatol. 2002, 26 (ane): 25-xxx.

-

Gardosi J, Mul T, Mongelli Yard, Fagan D: Assay of birthweight and gestational age in antepartum stillbirths. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998, 105: 524-530.

-

Wessel H, Cnattingius S, Bergstrom Southward, Dupret A, Reitmaier P: Maternal risk factors for preterm and depression birthweight in Republic of cape verde. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1996, 75 (4): 360-366.

-

Conde-Agudelo A, Belizan JM, Diaz-Rossello JL: Epidemiology of fetal death in Latin America. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000, 79: 371-378. x.1034/j.1600-0412.2000.079005371.x.

-

Osman NB, Challis One thousand, Cotiro M, Nordahl G, Bergstöm S: Perinatal Event in an Obstetric Cohort of Mozambican Women. J Trop Pediatr. 2001, 47: xxx-38. 10.1093/tropej/47.one.thirty.

-

Feresu SA, Welch Yard, Gillespie B, Harlow SD: Incidence of and Sociodemographic Risk Factors for Stillbirth, Pre-term birth and Low Birthweight in Zimbabwean Women. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2004, 18: 154-163. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2003.00539.x.

-

Moyo SR, Tswana SA, Nystrom Fifty, Mahomed One thousand, Bergstrom S, Ljungh A: An Incident Case-Referent Study of stillbirths at Harare Motherhood Hospital: Socio-Economic and Obstetric Risk Factors. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1994, 37: 34-39.

-

Kambarami RA, Chirenje 1000, Rusakaniko South, Anabwani G: Perinatal mortality rates associated socio-demographic factors in two rural districts in Zimbabwe. Cent Afr J Med. 1997, 43 (6): 158-162.

-

Iliff PJ, Kenyon Northward: Perinatal mortality statistics in Harare 1980–1989. Cent Afr J Med. 1991, 37 (5): 133-136.

-

Iliff PJ, Bonduelle MM, Gupta V: Changing stillbirth rates: quality of care or quality of patients?. Cent Afr J Med. 1996, 42 (4): 89-92.

-

De Muylder X: Perinatal mortality audit in Zimbabwean district. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1989, three: 284-293.

-

Department of Reproductive Wellness Research, World Wellness Organization: Guidelines Overview Safe Maternity Needs Assessment (WHO Publication No. WHO/RHT/MSM/96.18 Rev.one). 2001, Geneva, Switzerland: Earth Wellness Organization

-

Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M: A Usa National Reference for Fetal Growth. Obstet Gynaecol. 1996, 87 (two): 163-168. ten.1016/0029-7844(95)00386-X.

-

Platt RW, Joseph KS, Anath CV, Grondines J, Abrahamowicz 1000, Kramer MS: A proportional Hazards Model with Time-dependent Covariates and Time-varying Effects for Analysis of Fetal and Infant Expiry. Am J Epidemiol. 2004, 160: 199-206. ten.1093/aje/kwh201.

-

Joseph KS: Incidence-based measures of birth, growth restriction, and decease can free perinatal epidemiology from erroneous concepts of hazard. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004, 57: 889-897. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.11.018.

-

Yudkin PL: Risk of unexplained stillbirth at different gestational ages. Lancet. 1987, 8543: 1192-1194.

-

Munjanja South, Lindmark 1000, Nystrom L: Randomised controlled trial of reduced-visits programme of antenatal care in Harare, Zimbabwe. Lancet. 1996, 348 (92024): 364-369. x.1016/S0140-6736(96)01250-0.

-

Cheung YB: On the Definition of Gestational-Age-specific Mortality. Am J Epidemio. 2004, 160: 207-210. x.1093/aje/kwh202.

-

Klebanoff MA, Schoendorf KC: Invited Commentary: What'due south then bad about curves crossing anyhow?. Am J Epidemiol. 2004, 160: 211-212. 10.1093/aje/kwh203.

-

Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR: Invited Commentary: Assay of Gestational-Historic period-specific Mortality – On what Biologic Foundations?. Am J Epidemiol. 2004, 160: 213-214. ten.1093/aje/kwh204.

-

Aiken CG: The causes of perinatal mortality in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Cent Afr J Med. 1992, 38 (7): 263-281.

-

Tshimanga M, Makunike B, Wellington M: An audit of motherhood referrals in labour from primary health intendance clinics to a cardinal hospital in Harare, Zimbabwe. Cent Afr J Med. 1997, 43 (10): 279-283.

-

Chalumaeau M, Bouvier-Colle Thou, Breart G, the MOMA Group: Can clinical hazard factors for late stillbirth in Westward Africa be detected during antenatal care or only during labour?. Int J Epidemiol. 2002, 31: 661-668. 10.1093/ije/31.3.661.

-

Kambarami RA, Manyame B, Macq J: Syphilis in Murewa District, Zimbabwe: an old problem that rages on. Cent Afr J Med. 1998, 44 (nine): 229-232.

-

Feresu SA, Woelk GB, Harlow SD: Risk factors for Prematurity at Harare Motherhood Hospital, Zimbabwe. Int J Epidemiol. 2004, 33: 1194-201. x.1093/ije/dyh120.

-

Axemo P, Liljestrand J, Berstrom S, Gebre-Medhin : Aetiology of Late Fetal Expiry in Maputo. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1995, 39: 103-109.

-

Fawcus SR, Crowther CA, Van Baelen P, Marumahoko J: Booked and unbooked mothers delivering at Harare Maternity Hospital, Zimbabwe: a comparing of maternal characteristics and fetal upshot. Cent Afr J Med. 1992, 38 (x): 402-408.

-

Galvin J, Woelk GB, Mahomed M, Wagner N, Mudzamari Southward, Williams MA: Prenatal care utilization and fetal outcomes at Harare maternity Hospital, Republic of zimbabwe. Cent Afr J Med. 2000, 47 (4): 87-92.

-

UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/Earth Bank Special Plan of Research Development and Enquiry Training in Homo Reproduction: Who Antenatal Intendance Randomized Trial: Manual for the Implementation of the New Model. 2002, Geneva: Globe Health Organization

-

Fretts RC, Schmittdiel J, Mclean FH, Usher RH, Goldman MB: Increased maternal historic period and risk of fetal expiry. Northward Engl J Med. 1995, 333 (15): 955-957. 10.1056/NEJM199510123331501.

-

Fretts RC, Usher RH: Causes of Fetal Death in Avant-garde Maternal Age. Obstet Gynaecol. 1997, 89 (i): 40-45. ten.1016/S0029-7844(96)00427-nine.

-

Waldoer T, Haidinger G, Langgassner J, Tuomilehto J: The upshot of maternal historic period and nascency weight on the temporal trend in stillbirth rate in Austria during 1984–1993. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1996, 108 (20): 643-48.

-

Feresu SA, Gillespie BW, Sowers MF, Johnson TRB, Welch Grand, Harlow SD: Improving the assessment of gestational age in a Zimbabwean population. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002, 78: 7-xviii. ten.1016/S0020-7292(02)00094-2.

-

Feresu SA, Harlow SD, Gillespie B, Welch K, Johnson TRB: Birthweight Adjusted Dubowitz methods: Reducing Misclassification of Assessments of gestational age in a Zimbabwean population. Cent Afr J Med. 2003, 49 (nos 5/six): 47-53.

-

Platt RW, Ananth CV, Kramer MS: Analysis of neonatal mortality: is standardizing for relative birth weight biased?. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2004, 4 (9): 1-ten. [http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/iv/9]

-

Kulmala T, Vaahtera K, Ndekha M, Koivisto AM, Cullinan T, Salin ML, Ashorn P: The importance of preterm births for peri- and neonatal mortality in rural Malawi. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2000, 14 (three): 219-226. x.1046/j.1365-3016.2000.00270.x.

-

Kaushik SL, Parmar VR, Grover Due north, Kaushik R: Neonatal mortality charge per unit: relationship to birth weight and gestational age. Indian J Pediatr. 1998, 65 (3): 429-433.

Pre-publication history

-

The pre-publication history for this paper tin be accessed hither:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/5/9/prepub

Acknowledgements

Funding for the research was from the University of Michigan, University of Republic of zimbabwe and W.One thousand. Kellogg Foundation. Nosotros thank the Harare Motherhood Hospital staff, and the Department of Community Medicine at the University of Zimbabwe for providing space and support during information collection. This project was partially supported by grant #D43-TW01276 from the Fogarty International Centre and the National Constitute of Child Health and Human Development. We acknowledge the piece of work washed by enquiry administration, Ms J Musengi, Ms D Matsika, Ms 1000 Sithole, Mrs. F Shonhiwa and Ms T. Feresu, and South Nardie for editing this manuscript.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(south) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

SF conceived of the study, participated in design of the study, carried out the data collection and all analyses and drafted the manuscript.

SD participated in conceiving and designing the study, directed the analysis of the study and reviewed the manuscript.

KW participated in the assay of the written report and formulated the probability functions used to construct the figures.

BG participated in the analysis of the study, reviewed models to calculate the relative risk, and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the terminal manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12884_2004_61_MOESM1_ESM.physician

Additional File one: Demographic and Obstetric Characteristics and Crude Risks of Stillbirth for xvi,023 Singleton Deliveries at Harare Maternity Hospital; October 1997 to September 1998 (DOC 43 KB)

12884_2004_61_MOESM2_ESM.dr.

Additional File 2: Adjusteda Demographic and Obstetric Characteristics and Risks of Stillbirth for 16,023 Singleton Deliveries at Harare Motherhood Hospital; October 1997 to September 1998 (DOC 42 KB)

12884_2004_61_MOESM3_ESM.doc

Additional File iii: Frequency of Stillbirth past Birth Weight and Gestational Age Categories for 17,072 Deliveries at Harare Maternity Hospital; Oct 1997 to September 1998 (Doc 62 KB)

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Feresu, S.A., Harlow, S.D., Welch, Thou. et al. Incidence of stillbirth and perinatal mortality and their associated factors amid women delivering at Harare Maternity Hospital, Zimbabwe: a cross-sectional retrospective analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 5, nine (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-5-9

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-five-9

Keywords

- Prenatal Care

- Perinatal Mortality

- Obstetric Intendance

- Agin Birth Outcome

- Normal Vaginal Delivery

Source: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2393-5-9

0 Response to "Sign a Stillborn Over to a Hospital What Became of the Baby"

Post a Comment